In many large organisations, alignment is pursued through meetings.

Calendars fill with refinement sessions, estimation workshops, backlog reviews, and alignment calls. These are conducted with the best of intentions. They are meant to prevent silos, to ensure shared understanding, and to create collective ownership of the work.

And yet, after months of such careful alignment, a familiar scene emerges.

A system behaves in a way nobody fully expects. A rule exists, but no one can say precisely where it is written. A decision was made, but the reasoning is scattered across tickets, emails, and memories. A new colleague joins and spends weeks discovering not what the system does, calmly and clearly, but who to ask.

The paradox is subtle: the organisation is rich in communication, but poor in institutional memory.

The hidden assumption behind agile alignment

Modern agile practice, especially in its institutionalised form, often treats meetings as the primary instrument of alignment.

Estimation sessions are not only about numbers; they are designed to trigger conversation. Refinement sessions are not only about tickets; they are meant to ensure shared understanding. The underlying belief is simple:

if we talk together, we will understand together.

This works remarkably well for certain kinds of work. Feature development, bug fixing, UI adjustments, and many forms of iterative implementation benefit from collective discussion. Tasks are comparable, skills are somewhat interchangeable, and the conversation itself produces clarity.

But there is another category of work that quietly resists this model.

When the work is not interchangeable

In large, complex programmes — especially in regulated environments — some tasks are not about producing features, but about shaping the conditions under which all features are produced.

Designing how specifications should be written. Defining how integration should be governed. Establishing how documentation, testing, and implementation relate to each other. Creating the structure that others will later inhabit.

This is expert work. It is architectural, structural, and often deeply experiential.

Here, alignment through estimation becomes oddly ineffective. Team members who are not familiar with the domain cannot meaningfully estimate the task. The expert’s judgement quietly becomes the reference point anyway. Time is spent discussing what cannot truly be democratised: specialised knowledge.

The meeting produces the feeling of alignment without necessarily producing understanding.

Meetings as a substitute for artefacts

Over time, one begins to notice something more fundamental.

Many of the meetings intended to create alignment are compensating for a different absence: the absence of clear, shared artefacts.

When rules live in conversations rather than documents, we must talk about them repeatedly. When specifications are scattered across tools and formats, we must explain them again and again. When decisions are not attached to the artefacts they affect, we must reconstruct their history in meetings.

The meeting becomes a repair mechanism for weak institutional memory.

In this sense, alignment through meetings is not the root solution. It is a workaround.

Artefacts as carriers of alignment

There is another way alignment can emerge — not through repeated conversation, but through shared reference.

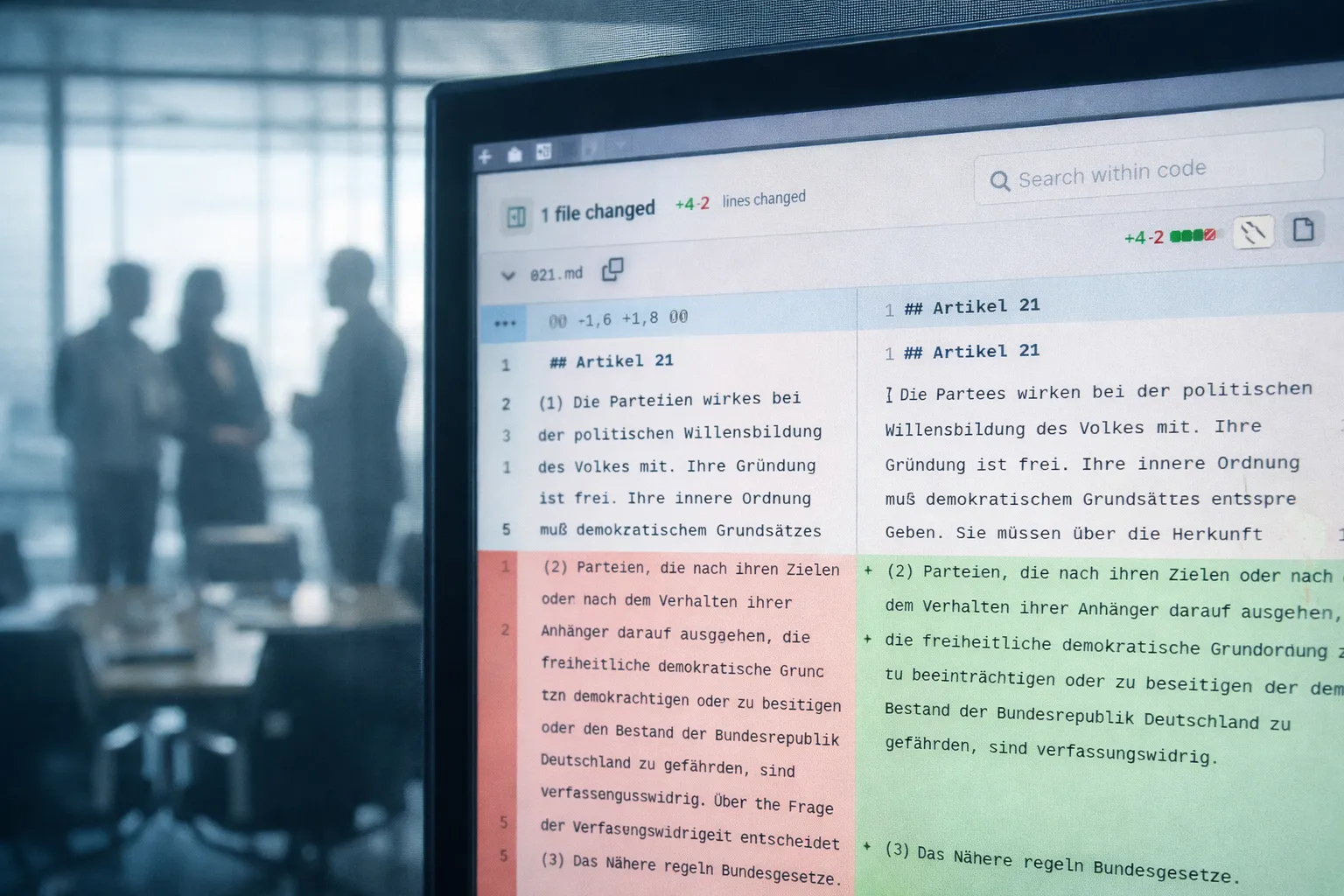

When specifications, rules, and integration contracts are written in structured, versioned text and live alongside the systems they describe, something changes.

One can see who changed what, when, and why. Discussions remain attached to the artefacts they concern. Differences between versions become visible at a glance. New colleagues can read the history of a system rather than reconstruct it from other colleagues’ memory.

In such an environment, alignment does not need to be performed as often in meetings, because it is continuously present in the artefacts themselves.

Reading replaces asking. History replaces recollection. Structure replaces explanation.

A shift in where alignment happens

This is not an argument against agile practice. It is an observation about where its energy is best spent.

Agile ceremonies work well when the bottleneck is coordination between people. They work less well when the bottleneck is clarity of artefacts.

When artefacts are weak, meetings are necessary. When artefacts are strong, meetings become lighter, shorter, and less frequent — people no longer need to reconstruct what is already visible.

Alignment moves from the meeting room to Git repository.

Institutional memory as infrastructure

In large institutions, the greatest productivity gain rarely comes from new features or new tools. It comes from reducing the friction of understanding what already exists.

This is where seemingly simple tools — plain text, version control, structured documentation — become unexpectedly powerful.

They do not look like innovation. They do not appear in strategy slides. However, they quietly transform how organisations remember.

And once an organisation can remember clearly, it can move forward with far less effort.

From conversation to coherence

Perhaps the most significant shift is psychological.

When alignment depends on meetings, people feel dependent on each other’s availability. When alignment depends on artefacts, people feel empowered by shared clarity.

Work becomes less about synchronising calendars and more about contributing to a common, visible structure.

In this way, governance, documentation, testing, and implementation stop being separate activities. They become facets of the same system.

Alignment is no longer something we repeatedly create. It is something we maintain by design.

If this perspective resonates, it may be worth asking, in your own environment:

Are we aligning through meetings because we must — or because our artefacts are not yet doing enough of the work for us?