I. After the Centre

When this series last ended in 1969, Kenneth Clark left behind an unease. The modern world possessed immense energy and extraordinary technical power, yet what earlier civilisations had assumed almost instinctively — a centre — was no longer obvious.

In the decades since, progress has only accelerated. Communication has become global, calculation instantaneous, and information pervasive. These achievements deserve admiration. Yet we have learned that power is distinct from civilisation, just as abundant energy is distinct from order. Without shared forms—without agreement about how knowledge is shaped, preserved, and handed on—progress is empty motion.

And yet, civilisation held.

We did not abandon the physical world — we still enjoy good food, need sleep, and seek shelter from the cold. But the centre of our shared life began to shift. Gradually, attention shifted away from the sheer accumulation of things toward the structures that made cooperation possible: the systems by which knowledge was recorded, exchanged, tested, and carried forward. Within these largely unseen arrangements, civilisation found new means of continuity.

It is this reconfiguration — subtle, incomplete, and still fragile — that I want to consider here.

II. The Invisible Commons

In truth, this development returns us to an older tradition. Civilisation has rarely been sustained by authority alone. Even in periods of strong government or settled belief, its real work has relied on voluntary association—on the willingness of people to cooperate around a purpose worth sustaining.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this impulse animated the Republic of Letters. It was a territory defined by ink. Ideas travelled slowly between desks and studies, often ignoring the wars of their kings. A philosopher in Paris could dispute first principles with a mathematician in Cambridge; a writer in exile could remain part of a continental conversation.

They shared no ruler and acknowledged no single doctrine. They differed sharply in temperament and belief, yet understood themselves to be citizens of the same country. What bound them were standards: of evidence, of argument, and of courtesy. Knowledge, in this world, was not a possession to be hoarded, but a light to be shared.

AI-generated composite inspired by early modern European thinkers (René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Isaac Newton, Voltaire, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza).

For a long time, this spirit receded from view. The industrial age taught us the virtues of enclosure. We built fences around land, walls around factories, and increasingly, legal barriers around ideas. Where value was material, scarce, and costly to produce, ownership became the principal means of recognition and defence — and it still serves us well.

Toward the end of the twentieth century, however, a curious pattern re-emerged. Among scientists, engineers, and students working at the edges of a new digital machinery, the established forms of enclosure proved inadequate. Building structures of vast complexity and reach required a different posture: one grounded in participation as much as possession.

Gradually, and without central direction, new commons took shape. These are spaces where the work of one person was offered to the use of many; where contribution outweighs possession; and where rules are sustained by shared understanding. These arrangements rely on a quiet optimism — the belief that human beings, given the opportunity, would prefer to build together rather than to destroy alone.

They remain fragile. They are easily misunderstood, and easily neglected. Yet upon this assumption — modest, generous, and profoundly human — much of our contemporary civilisation has come to rest.

III. Tim Berners-Lee — The Act of Courtesy

The reordering of our digital world began, fittingly, not in a marketplace, but in a place of inquiry. By the late 1980s, computers were already powerful and networks increasingly widespread, yet information remained confined within isolated systems. To move from one to another required a change of language, protocol, or machine. Knowledge existed, but it did not yet flow.

Tim Berners-Lee, then working as a physicist and engineer, recognised in this fragmentation something deeper than technical inconvenience: an obstacle to the exchange of ideas. He proposed a simple remedy: a way for documents on different computers to be linked together, addressed through common rules, and retrieved by anyone connected to the network. The means were spare—uniform addresses, shared protocols, plain documents.

At the time, the prevailing logic was clear. New technologies were enclosed, patented, licensed. They became assets, and then territories. This approach had shaped much of the modern world, and often served it well. But Berners-Lee declined it. He did not claim ownership of the Web, nor place it behind fees or permissions. Instead, he released its protocols openly, allowing anyone to use and build upon them.

The decision appeared almost administrative. In retrospect, it was decisive. A system intended to connect the world could not begin by demanding entry. By refusing to own the Web, Berners-Lee allowed it to function as neutral ground — a public space without a gatekeeper.

Clark once described courtesy as the discipline by which we restrain our own claims in order to make room for others. In this sense, the Web was an act of courtesy expressed in technology. Its enduring power lies as much in its refusals as in its capabilities.

From that restraint flowed much that followed.

IV. Linus Torvalds — Order Without Command

Photograph published by The New Yorker, 2018.

If the Web was founded on an act of courtesy, the system that made it durable was built on something more bracing: an uncompromising respect for how things actually work.

In the early 1990s, Linus Torvalds, then a student at the University of Helsinki, began writing the core of an operating system. The impulse was practical rather than ideological. His professor, Andrew S. Tanenbaum, had created MINIX—an elegant, Unix-inspired teaching system—so that students could study the anatomy of an operating system. But MINIX was not intended for everyday use, and it did not run on Torvalds’s own machine in the way he required.

Out of a mixture of curiosity and irritation, he decided to build something that would.

What is striking, even in hindsight, is how complete that decision already was. The earliest public release of Linux was more than a sketch. It was a working kernel: multitasking, memory-managed, architecturally coherent. It revealed, from the outset, a deep and practical understanding of how operating systems behave under real constraints. Authority, in this case, did not need to be asserted. It was visible in the code.

A young student programming without audience, funding, or design committee.

When the system reached a point where others might find it useful, Torvalds released it with a plain invitation: use it, improve it, tell me what breaks.

There was no manifesto and no appeal to higher ideals. There was simply work to be done.

He did not come to this characteristic pragmatism from a vacuum. He had begun programming at the age of eleven, and grew up in a household where intellectual argument was neither rare nor intimidating. His parents were journalists, his grandfather a statistician. Ideas, facts, and disagreement were part of ordinary conversation, not marks of authority.

He was named, with ambiguity, after the scientist and peace activist Linus Pauling—or, as he later remarked, perhaps equally after the Linus from Peanuts. The joke is revealing. It suggests a temperament comfortable with seriousness, but resistant to solemnity; respectful of ideas, but impatient with reverence.

That impatience would become legendary. Torvalds was blunt, intolerant of sloppy reasoning, and openly dismissive of work that failed to meet clear standards. In another setting, such a manner might have proved destructive. In this one, it served a clarifying purpose.

What emerged around Linux surprised almost everyone. Programmers from across the world began to contribute—not because they were commanded to, but because the standards were unmistakable, and the results were useful and visible. Authority arose where competence was demonstrated. Disputes were frequent, sometimes fierce, but they were settled by the quality of the work itself.

Linux showed that order need not depend on hierarchy. It could arise from shared standards, rigorous review, and a willingness to reject what failed to meet them. The collaboration survived and thrived, because disagreement was channelled into improvement rather than paralysis.

Today, the result of that discipline is so pervasive that it has become effectively invisible. Linux runs the watch on a wrist and the rocket in the void; it governs the flow of global finance and the monitors of intensive care. The banker, the surgeon, and the statesman rely upon it every second of their lives, yet few could name it—or the man who began it. It has become the silent, universal substrate of modern civilisation.

As the project grew, a new problem appeared. The accumulation of changes—branching paths, conflicting versions, overlapping experiments—threatened to overwhelm its own history. Torvalds’s response was direct. He built a tool to address the problem properly, from first principles, in a matter of days.

He called it Git.

It is an obstinate word for an obstinate tool. Torvalds explained the choice with a certain wry self-knowledge: “I’m an egotistical bastard, and I name all my projects after myself.” This joke was a refusal to pretend otherwise.

Git altered the way collective memory was handled. Instead of a single, authorised record guarded at the centre, it allowed every participant to hold a complete and inspectable history. Experiments could diverge without endangering the whole, and failures could be acknowledged without erasure. Continuity was preserved without supervision, and responsibility without humiliation.

In civilisational terms, this was no small matter. Git provided what large institutions have always struggled to maintain: a reliable memory that tolerates error while remaining accountable. It made cooperation at scale possible, and more importantly, sustainable.

Torvalds rarely spoke of these achievements in elevated language, and perhaps that is part of their strength. He distrusted abstraction and disliked ceremony. Yet through an insistence on standards—sometimes uncomfortable, often demanding—he demonstrated that order can emerge without command.

If Berners-Lee’s restraint made room for others to enter, Torvalds’s discipline made it possible for them to stay—and to build.

V. The Open Source Ascent

AI-generated scene depicting collective software work—reading, review, and writing—within shared technical infrastructure. The figures are representative, and include allusions to influential contributors whose work shaped the open source movement beyond what this essay can fully recount.

We have spoken of individuals, but civilisation does not advance by solitary effort alone. Ideas endure only when they are taken up, tested, corrected, and carried forward by others. What followed the release of the Web and Linux was therefore not an anomaly, but an ascent — collective, distributed, and largely unplanned.

By the usual measures of self-interest, it should not have worked. There was no payroll, no central authority, and no clear promise of reward. Yet across universities, companies, and bedrooms, programmers began to contribute their labour to shared projects, refining one another’s work with a seriousness usually reserved for long-established institutions. What bound them was not ideology, but standards: the work had to function, and it had to withstand scrutiny.

Out of this discipline grew structures capable of sustaining effort at scale. Organisations such as the Linux Foundation, the Apache Software Foundation, and the Eclipse Foundation did not command creativity so much as shelter it—providing neutral ground where competing firms, independent developers, and public institutions could collaborate without surrendering control to any single interest.

These great foundations, joined by a constellation of individual efforts, quietly became both the backbone and the surface of the modern world. They supplied the invisible servers and operating systems upon which industry depends, extending that order to the programming languages, development tools, and utility applications that weave through the texture of daily life.

Earlier civilisations had known voluntary scholarship and shared intellectual purpose. What they lacked were the means to sustain such efforts beyond a narrow elite. The Republic of Letters relied on slow correspondence and fragile memory. Here, by contrast, the technical conditions had fallen into place. The Web offered a common space of address; Git provided a disciplined way to coordinate distributed work while preserving the history of every path taken; and systems like Linux supplied a stable, universal substrate at the machine level.

Together, these tools did not create generosity — but they gave it form, continuity, and reach. Contribution could be preserved rather than lost, disagreement recorded rather than erased, and improvement accumulated without dissolving into chaos. For the first time, cooperation among strangers could be both rigorous and durable.

What emerged was neither a utopia nor a rebellion against institutions. It was a practice — demanding, sometimes severe, but remarkably productive. Authority arose where competence was demonstrated, and responsibility where work was accepted. In this way, the invisible commons acquired not only energy, but memory.

It was a modest beginning, and an unfinished one. But it marked something new in the history of civilisation: a means by which collective effort could outlast enthusiasm, survive disagreement, and leave behind structures strong enough to build upon.

A way toward permanence.

VI. Larry Page & Sergey Brin — Curiosity as Civic Infrastructure

Civilisations have always faltered not for lack of knowledge, but for lack of finding it. The great library of Alexandria held its wealth in scrolls; the digital commons held it in billions of fragments, scattered and multiplying. The crisis was one of orientation.

It required a particular kind of genius to address this: not the genius of the poet, who creates new worlds, but the genius of the librarian, who imposes order upon the old.

In the mid-1990s, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, then students at Stanford University, approached this problem with an engineer’s impatience with chaos. They recognised that within the tangled mess of the Web, there lay a hidden structure. Links were more than mere decorations; they were judgments. Every reference implied trust, relevance, and attention. If these signals could be measured, the cacophony of human knowledge might order itself, without the need for a central censor.

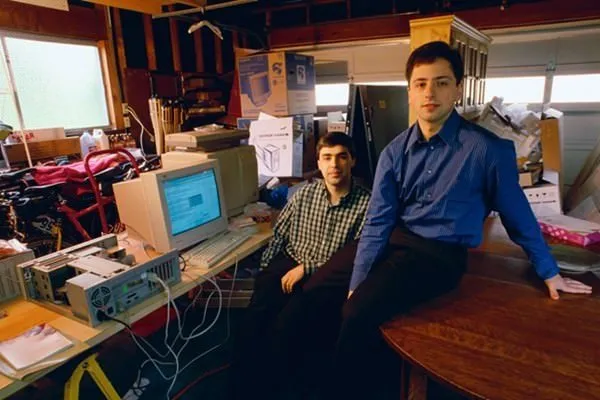

Page and Brin set out to implement this theory with their own hands. Much of the early system — from the crawling of pages to the ranking of results — was coded by them, tested against the crushing weight of the real Web, and refined through sleepless nights. Their authority rested on a simple, undeniable premise: they had made the thing work.

Their ambition, expressed with an engineer’s disarming simplicity, was among the broadest in human history:

Basically, our goal is to organize the world’s information and to make it universally accessible and useful.

Few statements have carried such consequence with so little ornament.

Two engineers confronting the problem of orientation at human scale, before search became infrastructure.

Photograph via The Internet History Podcast.

What emerged was more profound than a commercial search engine — and more consequential than its creators could fully foresee. It was a new cognitive infrastructure, the likes of which had never existed. Questions that once required travel, training, or immense patience could now be answered in moments. Curiosity ceased to be a privilege of the leisured class. It became a habit of the multitude.

The organisation they built, Google, quickly outgrew its original function. To organise the world’s information at planetary scale required inventions far beyond indexing. It required a new kind of architecture: distributed computation, fault-tolerant systems, and coordination at unprecedented scale. In solving its own problems, Google was forced to become a builder of new civic infrastructure.

Here, the spirit of the commons reasserted itself in an unexpected form. Having built their edifice upon the open foundations of Linux, Page and Brin began to return the scaffolding to the world. They released Android, placing a general-purpose operating system into billions of hands; they gifted Kubernetes, providing a common language for managing complexity across industries.

These were acts of calculated necessity. They understood that no single organisation—not even one as vast as theirs—could sustain such complex systems alone.

This created a productive tension. Google became both a citadel of proprietary power and a primary engine of open infrastructure. It demonstrated that in the modern age, collaboration is more than an ideal; it is a structural necessity.

Such power inevitably casts shadows. To control the map is to influence how others move, and the risks of such centralisation are real. Yet the original impulse remains unmistakable: a belief that knowledge, once organised, should belong to everyone — and that the tools required to manage this complexity should not be locked behind walls.

Page and Brin belong, in Clark’s sense, among the God-given geniuses who realised their own ambitious visions. They recognised a crisis of confusion in the civilisational record, and with their own craft, built a working answer.

As builders rather than figureheads. Photograph © Kim Kulish / Corbis Historical / Getty Images.

Curiosity, once given structure, became infrastructure.

What followed would test how the use of such infrastructure should be judged — and at what human cost.

VII. Aaron Swartz — The Conscience of the Commons

If the story ended with the triumph of the Web and the ordering of the map, we might be tempted to call it a victory. But history suggests otherwise. When the pace of civilisation accelerates, it often leaves its institutions behind. And in that widening gap, there are casualties.

Aaron Swartz stood squarely in that gap.

Swartz (age 16) and Lessig at the launch party for Creative Commons. Photograph by Gohsuke Takama, originally posted to Flickr and licensed under CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Born in 1986 near Chicago, Swartz was a prodigy, a builder, and — in a deeper sense — a conscience. He belonged naturally to the world of the commons we have been describing, fluent in its technical languages and serious about its moral claims. For him, openness was a principle to be acted upon.

His contributions began with something deceptively modest. He helped create Markdown, a syntax that appears, at first glance, to be nothing more than plain text. Yet this simplicity was a philosophical choice. By stripping away the complex, fragile interfaces of modern word processing, Markdown liberated the writer to focus on the hierarchy of ideas rather than their ornamentation. It restored a necessary discipline to the act of writing, ensuring that the structure of an argument remained visible, honest, and distinct from its display.

The implications of this choice extended far beyond the quiet of the study. Swartz understood that for knowledge to endure, it must be separable from the tools used to create it. Because Markdown treated text as structured data, a document was no longer a dead artifact, but an active component of a system. A specification written in this way could be transformed, by the simplest of scripts, into a website, a technical manual, or even executable code. It opened the way for streamlining the chaotic passage from abstract policy to concrete production, creating an unbroken chain between intention and execution.

In this sense, Markdown pointed toward a form of civic legibility: a way in which the vast records of society—its laws, its data, its history—might remain intelligible to both human eyes and machine logic, safe from the rot of proprietary obsolescence. It was a small tool, but it became the essential mortar for a civilisation built on code.

Swartz’s concern for access did not end with tools. He saw that while the machinery of the commons had become open, many of the great storehouses of human knowledge remained closed. Scholarly research — much of it publicly funded — was locked behind paywalls, accessible primarily to those already inside the gates. To Swartz, this inefficiency rose to the level of moral error.

Photograph originally published by DNAinfo New York, January 2013. Source: DNAinfo.

His response was literal and uncompromising. In 2011, he attempted to make available a large body of academic work, not for profit, but as an assertion of principle. It was an act of civil disobedience, closer in spirit to the old librarians than to the modern hacker stereotype. Where the digital world saw a custodian of knowledge, the institution saw a violator of rules.

The collision was severe. Swartz encountered a legal and prosecutorial machinery calibrated for deterrence rather than judgment, and example rather than proportion. The weight of the response far exceeded the scale of the act. What followed is well known, and remains difficult to contemplate.

It would be easy, at this point, to simplify the story — to assign villains and heroes, to turn tragedy into rhetoric. That would be a mistake. The institutions acted from procedure, Swartz from conviction. What failed here was something more elusive: a shared understanding of how ideals, once embedded in technology, should be reflected in law.

Clark once insisted that civilisation depends not only on knowledge, but on sympathy — on the capacity to recognise ourselves in others. The tragedy took the form of a collision: between a commons that had learned to move, and institutions that had not yet learned how to follow. Swartz’s life and death force an uncomfortable question: whether a society that builds its future on openness can afford to treat its most literal adherents as adversaries.

His story marks the point at which the invisible commons ceased to be merely a technical achievement, and became a moral test. It revealed that access, order, and power cannot be aligned by engineering alone. They require judgment and restraint — and, above all, a sense of proportion.

In the years that followed, the shock of this failure was not entirely absorbed in silence. Laws were re-examined, prosecutorial practices questioned, and the assumption that access could be criminalised without consequence began, slowly, to weaken. Institutions did not become wiser overnight — but they became more aware.

Civilisation learns unevenly, and often at great cost — usually after the fact. Its progress has rarely depended on perfect obedience, and still less on moral comfort. Again and again, it has been forced forward by individuals willing to test the distance between what is lawful and what is just — and to bear the consequences of that test.

Any consolation that remains lies in memory. Swartz’s insistence did not vanish with him. It entered the moral consciousness of the commons itself, where future generations may yet recognise that law, like technology, cannot remain untouched by human consequence.

In February 2025, a bust of Aaron Swartz was unveiled in the lobby of the Internet Archive in San Francisco — an institution dedicated to preserving the world’s knowledge and keeping it accessible. Its placement is telling: among readers, archives, and use, rather than courts or seats of power. It marks no victory, announces no verdict, and offers no absolution.

Photograph published by The San Francisco Standard.

It simply reminds those who pass beneath it that the commons was not built by compliance alone — and that civilisation, if it is to endure, must always leave room for conscience to speak before the law has learned how to listen.

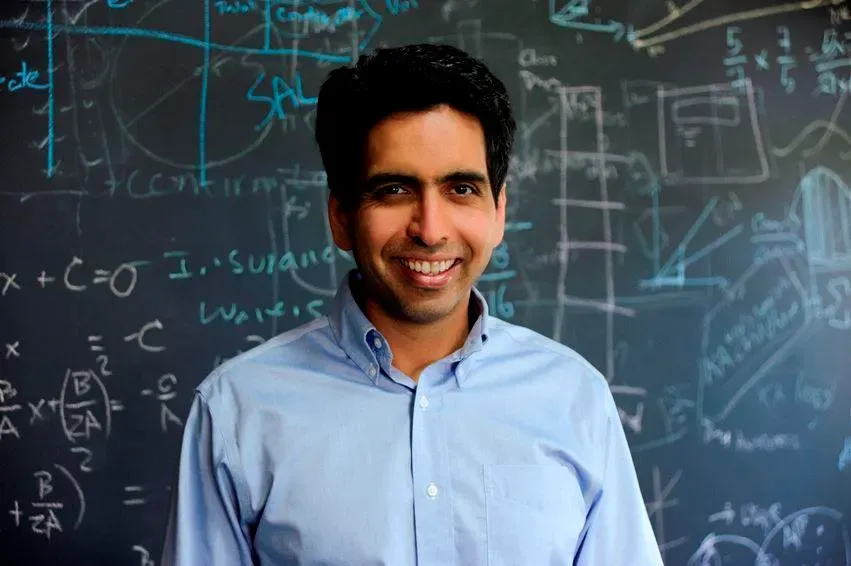

VIII. Sal Khan — Explanation as a Civic Act

After the moral strain of collision, it is necessary to return to first principles — this time of learning itself. Civilisation, after all, is not preserved by systems alone. It is preserved by transmission: by one mind taking the time to explain something carefully to another.

In 2004, Sal Khan began without a grand design to reform education. He was tutoring a cousin through the web. The subject was mathematics, and the medium he chose was austere: a black screen, a trail of coloured digital ink, and a voice. This created an aesthetic of pure concentration. The learner watched the thought itself unfolding in real time. Unencumbered by institutional theories or the language of disruption, the work relied entirely on the clarity of the explanation.

From this modest beginning grew Khan Academy — an online platform that functioned as a repository of patience. Its distinguishing quality lay in its tone. Concepts were broken down slowly, without embarrassment, and rebuilt step by step, treating the learner simply as an unfinished mind requiring only time and method to complete itself.

This approach addressed a failure that Clark had observed long before. He remarked that the so-called “top people” of earlier generations were often charming but poorly informed, while students in provincial universities were sharper, more curious, and more alert. The barrier between them was access—specifically, access to explanation.

Khan Academy demonstrated that high culture could be shared in its full complexity. Calculus, physics, economics, and history could be made intelligible while remaining rigorous. Explanation, when offered with care, became a form of respect.

Here, the tools of the invisible commons reached their most humane expression. The Web provided reach; search made discovery possible; open infrastructure kept costs low. Yet the motive force was the act of explanation itself. The teacher stood alongside the learner, treating the student as a capable mind, and making learning an act of invitation rather than one of ranking, filtering, or exclusion. This restoration of dignity remains one of the most consequential achievements of the digital age.

Sal Khan recording lessons for Khan Academy, Mercury News, 2016.

It is striking that a platform of this global reach and massive utility was founded on a single voice, repeated patiently thousands of times. Even as the project expanded, it retained this intimacy. While traditional schools carry responsibilities far beyond explanation, Khan proved that the continuity of knowledge operates independently of hierarchy. It advances most reliably where the responsibility for clarity is personal, continuous, and owned by a human voice.

In the end, his contribution reminds us of a truth often obscured by scale and abstraction: that alongside genius and conscience, civilisation depends upon explanation—offered freely, received humbly, and carried forward, one mind at a time.

Peroration — What Endures

We have traced a lineage defined less by doctrine than by a series of human gestures: restraint at the beginning, discipline in the making, generosity in collaboration, conscience under strain, and patience in explanation. Taken together, they suggest that the digital age grew around a distinct, if quiet, centre.

That centre resides beyond the reach of institutions, ideologies, or markets. It lives in a set of practices—ways of working, judging, and explaining—through which knowledge is made durable and meaning carried forward. They are largely invisible, easily neglected, yet without them the energy of an age leaves nothing that lasts.

Civilisation, as Clark understood, is defined by what it chooses to preserve. Permanence emerges through restraint; through the refusal to enclose what could be enclosed; through standards maintained without command; through explanations offered again, for the sake of someone still learning. Far from the habits of conquest, these are the gestures by which civilisation endures.

Yet they remain fragile. Tools may embody values, yet judgment cannot be automated. Institutions can preserve order, yet adaptation lags behind change. Genius may illuminate a path, yet sympathy and proportion determine how far that path can be followed. Again and again, endurance depends less on intelligence than on moral habit.

The digital world now shapes how we learn, how we work, how we remember, and how we judge one another. Whether it will lift civilisation — or merely accelerate it — remains an open question. The answer lies in the care with which these systems are used, extended, and restrained.

Civilisation has always been a provisional achievement. It must be built, maintained, and renewed by each generation. The invisible commons will endure only if it is treated as a trust.

And that, perhaps, is the measure of our moment: not whether we can build systems of astonishing complexity, but whether we can give them the forms, the sympathy, and the permanence required to make them worthy of civilisation itself.

Photograph via BBC Media Centre, from coverage of Civilisation: A Personal View.